A radium clock used in WWI. Photo credit: Collectors Weekly.

By Mary Rudzis, SCSU Journalism student

Mary Rudzis, journalism student at Southern Connecticut State University, reported this story in 2017 as part of Journalism Capstone coursework on World War I.

Products allowing soldiers to tell time in the trenches of World War I resulted in Connecticut women being poisoned. Known as the “radium girls” and centered in a Waterbury manufacturer, the women spent seven days a week, ingesting radium while they worked.

At the time, radium was used in products from chocolate to toothpaste, and factory workers were even painting it on their nails and clothing.

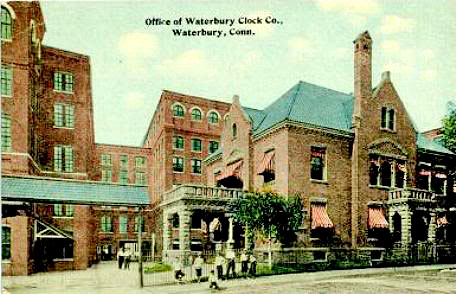

The Waterbury Clock Co. radium girls, as well as those who worked at radium factories in Newark, New Jersey and Ottawa, Illinois, entered the work force during World War I.

These women worked long hours for low wages painting tiny numbers on watch and clock faces with radio-luminescent paint, a glowing substance containing radium, a radioactive material harmful and even lethal when ingested, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry.

Workers were taught to “lip-dip” or “lip point,” which meant placing the tip of their paintbrush in their mouths before dipping it in the paint to make sure the numbers on dial faces were sharp and easy to read, according to “The Radium Girls” by Kate Moore.

In 1917, when the United States entered the war, the demand for radium watches and clocks skyrocketed, and “lots of dial-painters were motivated by the idea of helping the troops,” wrote Moore. Some 375 girls were recruited to paint dials in 1917. In 1918, “95 percent of all the radium produced in America was given over to the manufacture of radium paint for use on military dials,” according to Moore.

These watches were used in the trenches. When soldiers were wading through the mud and in the dark, they would be able to tell the time. Radium paint’s glow was relatively dim, but this was beneficial to soldiers because they could tell the time without revealing their positions.

The U.S. Radium Corp. factory in Orange, New Jersey won a contract by the U.S. military to make wrist watches instead of pocket watches with glowing hands. These watches later became popular with the general public.

“The fact that this stuff was glow-in-the-dark was an immediately useful idea for instruments that needed to be looked at at night,” said Gregory Kowalczyk, a chemistry professor at Southern Connecticut State University, “so, much of the watches and clocks and dials were used for the military in World War I.”

After the War ended, the U.S. Radium Corp. struggled with the loss of the military contract. Many radium girls resigned but were “quickly replaced,” according to Moore, because there was still a demand, though it was much less. The demand for radium watches and clocks again surged during World War II.

Managers and scientists of the radium dial factories were well aware of the dangers of ingesting and working with radium, even taking precautions such as wearing gloves and masks when handling the substance. However, they did not equip the women who worked in the factories with anything to keep them safe, despite knowing the risks, according Kowalczyk.

“By the time the radium companies were doing these watches, they knew it was harmful. They definitely knew that there were hazards associated with [radium] and they didn’t tell the women who were using [it],” said Kowalczyk.

Many women died as a result of “lip-dipping” and radium exposure and while it was too late for the workers, their deaths were a cautionary tale. By 1924, nine of the dial painters had died. They were all young women, mostly in their 20s, who were healthy prior to working in the factories with radio-luminescent paint.

When it came time for radium watches and clocks to be produced for soldiers in World War II, dial-painting was the “most feared occupation among young women,” according to Moore. Safety standards were introduced as a result of the original radium girls suffering conditions like anemia, inexplicable bone fractures, radium jaw, bleeding gums and extreme body pain.

The United States used more than 190 grams of radium for luminous dials during World War II, according to Moore. In World War I, fewer than 30 grams were used worldwide. However, even though more of it was being used, it was taken much more seriously and more precautions were taken.

The deaths of the radium girls, who provided a valuable product for the soldiers in World War I, shined a light on the dangers of radium use and, in the end, prompted more regulations for the substance to keep future workers safe.