July 13, 1913

We are in a village about two miles from Pau, with a lovely walk through the tall woods thither, and have been well taken care of by an ancien[t] professor and his wife. The first of August, we move into a new little apartment of our own, four rooms, just finished, lovely view, absolutely tranquil…last night… we had Gounod and S[c]hubert under a moon on the terrace [and a] long promenade that overlooks the mountains. Such loveliness, and rapture, and perfect happiness to me.

February 4, 1914

A month after vacationing with his daughter near Pau, James Robinson Smith clips an article from the Boston Evening Transcript. The headline reads: “Arms Menacing Europe: Grey Fears They Will Destroy Prosperity: Likely to Lead Civilization to Disaster.” Smith has set aside his civilized life as a writer, translator and scholar of literature for wartime work with the Red Cross. Born and raised in Hartford and educated at Yale, Smith now finds himself in London with the Red Cross’s Commission for Relief in Belgium. His daughter remains in Europe with him, despite the troubling political climate. Smith is a single parent; he lost his wife Martha one year after Lucinda’s birth. “Lucinda is very well and happy,” he writes to his mother. “I think I may have told you that a Belgian family sent her a doll’s trousseau of 160 pieces, all hand made.”

August 16, 1914

Smith and Lucinda return to the French village of Billère just outside of Pau. Smith writes his aunt Ella, “How much I would give if you and mama could have seen Lucinda sitting on a little wooden bench the other evening— I was late in getting home— and saying, without greeting me but looking up at the tall elms with the sunset on them: Aren’t the trees beautiful— the way they look out. She is more and more of a comfort… This morning she asked me: “Where does the sky go and what is the end of the sky? You don’t know because you haven’t traveled all over the world.”

September, 1914

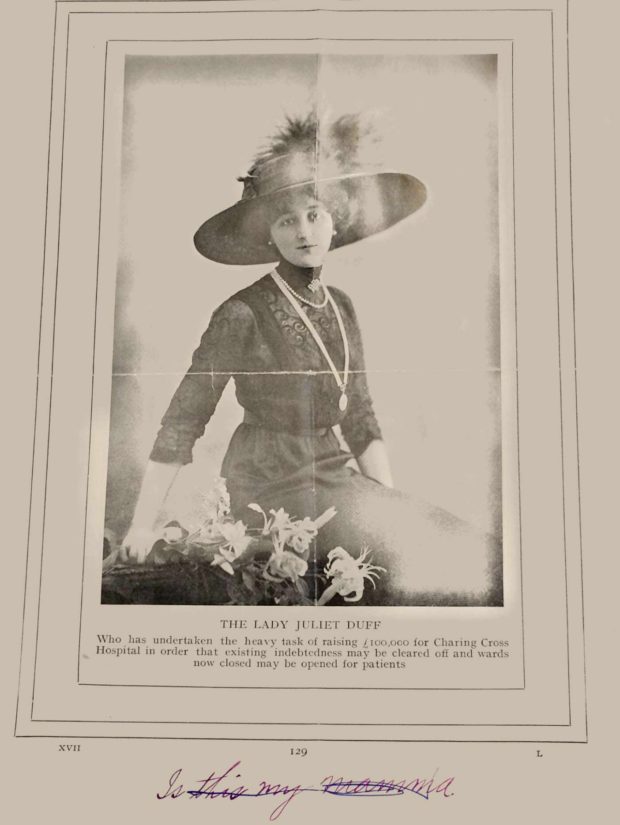

Page cut from a book, on which the question “is this my mamma” was written and scratched out, presumably by Lucinda

Trees that once stood tall against the sunset lie uprooted in the dust, and the sky matches the gray of pulpy corpses. The first great trenches of the Western Front have begun to disfigure the landscape of France, and villages that embodied such serenity in 1913 are stunned by the filthy, mechanical violence of the First World War. Swarms of prospective pilots descend upon Pau to attend the aviation school there, but to Smith, “Pau never seemed so lonely.” He has sent Lucinda back to the United States, where she now lives with his aunt Ella in Honolulu. “Is Lucinda on those hills?” Smith asks Ella, remembering a picture of Hawaii he’d seen in the Outlook. “Does grass grow in her yard on the hills? About what would a bungalow and two acres cost, the cheapest part of the hills but not too lonely, easy access to the rest of you?” Although Lucinda still calls him “father” whenever they communicate, “she says she gets it mixed up with farther away.” He asks her to keep sending snapshots.

April, 1917

Smith’s life is consumed by the war. In 1931, Smith will recall this as “one period during the war where the only solution to my life was to be ten men.” He has become something of an expert on European food rationing and the desperate conditions in Belgium, and his efforts are very much in demand. Yet with Lucinda gone, Smith finds time to assist destitute young girls living on the Belgian streets. With a father’s dedication and zeal, he works to secure relatively stable lives for these girls, even within the wartime chaos raging around them. Smith continues to seek out literary-minded company and make progress on his writing projects, but doing so has become increasingly difficult. Under Smith’s intel influence, one of the ‘street girls’ composes a poem on a thin slip of paper and gives it to him to keep: I slept! And a little vagrant breeze / Came dancing across the dawnlit-sea / Lifting the top of each swelling wave / Then letting it fall in glittering spray…

*

This poem, along with boxes of Smith’s correspondences and personal documents, has been preserved as part of the James Robinson Smith Papers in Yale University’s Manuscripts and Archives. One hundred years later, this collection affords insight into the experience of a Connecticut man’s struggle to maintain his identity as a scholar, a man, and a parent, as morbid convulsions seized the world.