By Jonathan Gonzalez and Kevin Crompton, SCSU Journalism students

Jonathan Gonzalez and Kevin Crompton, journalism students at Southern Connecticut State University, reported this story in 2018 as part of Journalism Capstone coursework on World War I.

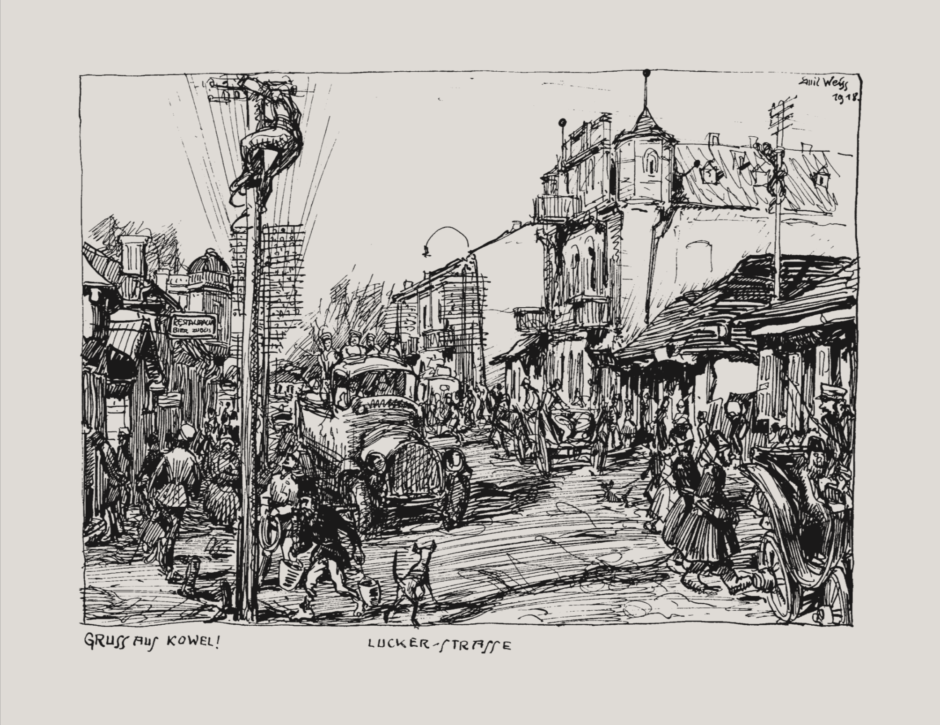

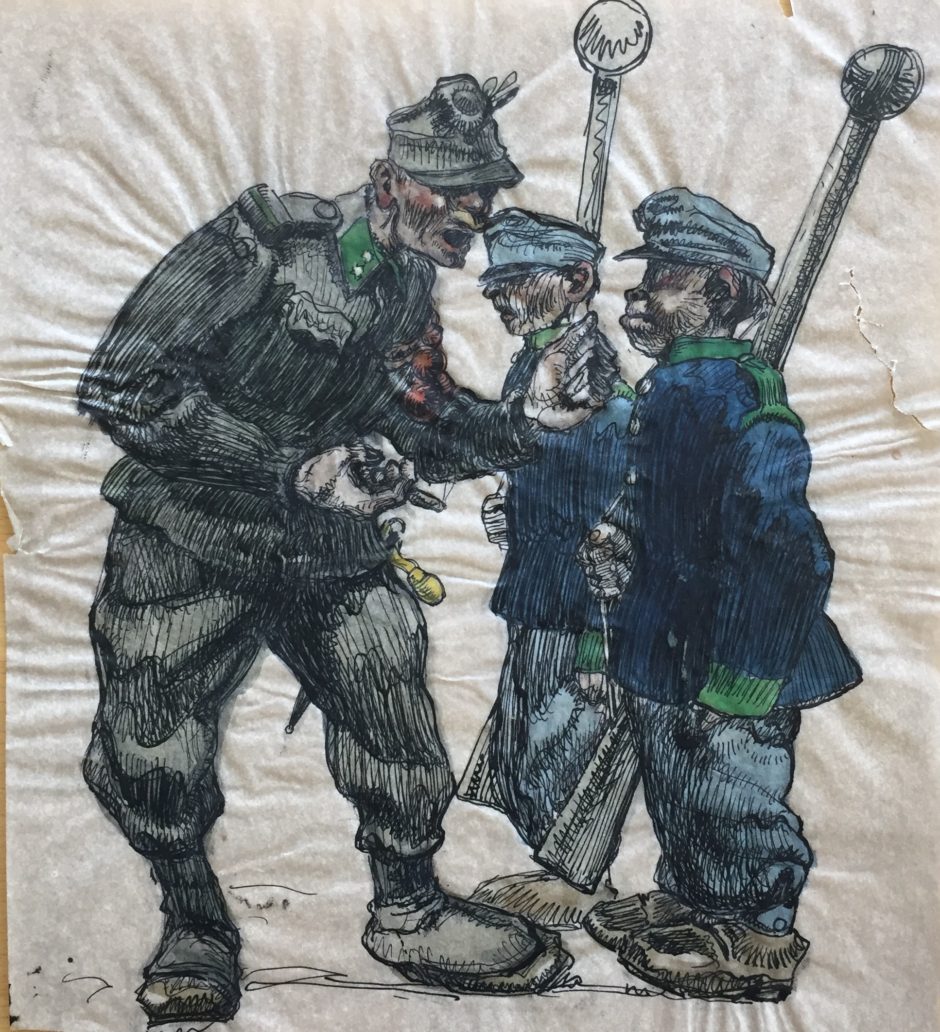

With just a pen and paper, Emil Weiss illustrated the daily struggles of life during World War I. Weiss was an artist and illustrator for the Austro-Hungarian 4th Army newspaper.

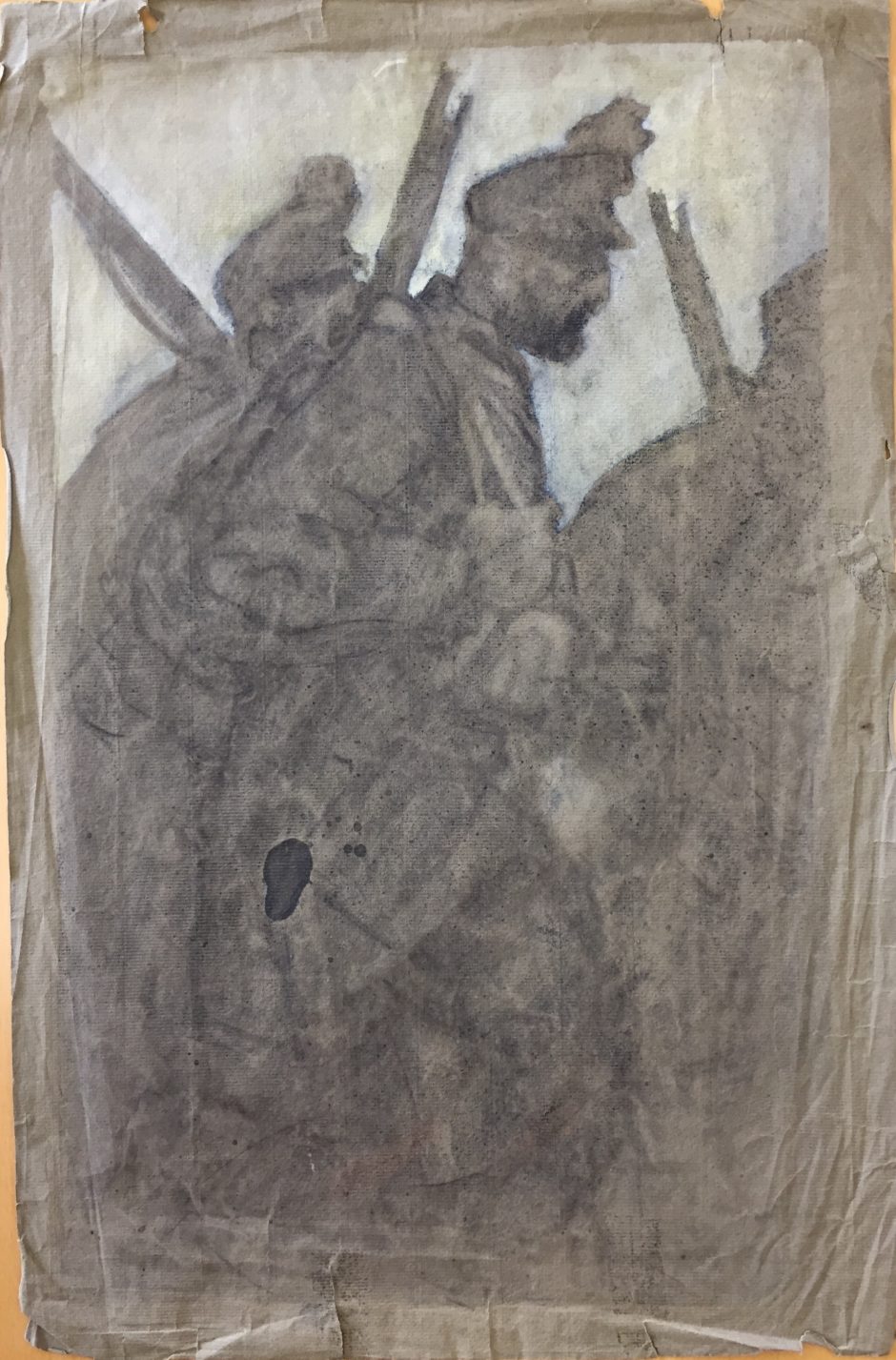

During his time as a soldier in the thick of battle, he documented everything around him from people and horses to weapons and infrastructure throughout the Great War.

“He was entirely self-trained. He just was incredibly acute at seeing things and he loved looking and drawing helped him look accurately,” said Alex White of Greenwich, Connecticut, chair of MPS Design Management at University of Bridgeport and grandson of Weiss.

During his time in the war, Weiss simply drew what he saw, including dead soldiers, horses and civilians he saw killed in front of him while fighting the Russians.

“Emil was in the 4th Army and soon became a famous personality for his work in the Army newspaper. All of Austria knew his drawings, posters and cards, and were all very proud of him,” said White.

Weiss’ artwork rapidly gained status in his homeland and people throughout Austria-Hungary saw his illustrations in the newspaper. His art provided an accurate portrayal of what the war was like for those who were unable to experience it first-hand.

“He had a reputation throughout his country,” said White.

Conscripted into the Army at 18, Weiss served from 1914 to 1918. His gift of drawing contributed to how the war was reported and served as recorded evidence of what was happening in Austria-Hungary during that time.

White said Weiss drew dozens of pictures on a daily basis. His drawings got better over time and with practice Weiss was able to produce better artwork than most of his peers at that time.

“I mean he was fooling around with space in a way that was not dealt with in those days very much yet and it was coming in basically in Prague and Vienna and Eastern Europe was developing. Germany was developing a new way of looking at space and art and he was involved in that by osmosis or something,” said White.

Weiss drew so much that that more than 30 years ago his son began to collect the pieces and turn them into an anthology series for his family’s consumption.

“My father — son of my grandfather obviously — an only child, made it his mission when after he turned 50 years old, to write a series of family histories. A series meaning about eight books, and there are three volumes dedicated to his father. One of them is about just simply his drawings,” said White.

White said that since Weiss drew every day, dozens of pieces of his work remain intact. Even pieces thought to have been lost ended up in the hands of Weiss’ family and relatives.

“My dad had a connection at the museum of decorative arts in Prague that would occasionally come across something that my dad had no idea existed, somebody would send him a copy of a poster or something that they had found,” said White.

White said there are “stylistic differences” in the way Weiss designed his illustrations. From 1914 to 1917 there is a visible shift to a more detailed vision of what wartime and the battlefield was like. With so many ways of expressing his views through his artwork Weiss was never at a loss for stylistic interpretation.

“He was constantly evolving his ability and his ways of seeing,” said White. “He would draw like this later on in life as well. He had so many tools at his disposal that I don’t know how he decided which way he was going to go on a particular day.”

White said Weiss’ artwork became one of his passions. It is what made his work timeless and a part of history.

“I’m not saying he was the Mozart of drawing by any means,” said White. “I’m saying he couldn’t help himself. To be alive was to draw. It was just as simple as that.”