By Sidney Jones, SCSU Journalism student

Sidney Jones, a journalism student at Southern Connecticut State University, reported this story in 2018 as part of Journalism Capstone coursework on World War I.

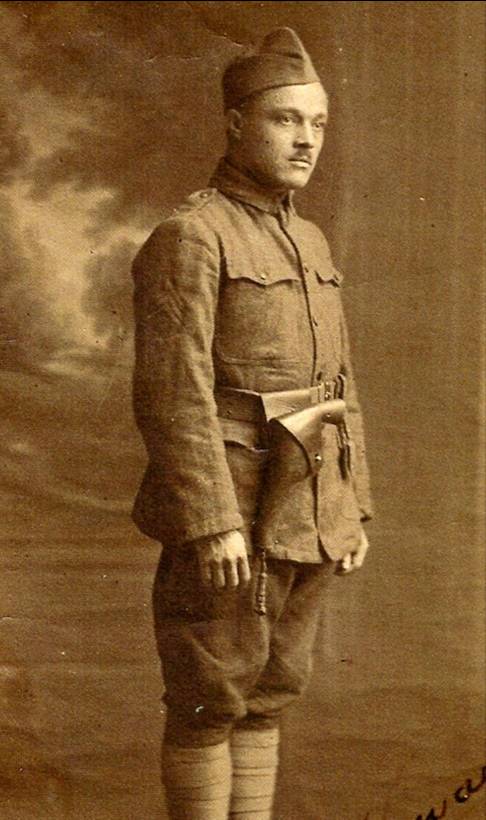

Howard P. Drew was a man who broke color barriers as a World War I soldier, Olympic athlete and the first black judge in Connecticut.

“There are few people today or in the past who can claim to be half the man Howard Drew was,” Vice President of the Board of Governors for USATF-New England, coach Larry Libow, said in an email. “It’s a shame that so few people know about him.”

As a soldier, Drew entered World War I in 1918 as a private in the Supply Company, 809th Pioneer Infantry Regiment, in the 88th Division of the U.S. Army. During his time in the war, he helped and trained the U.S. track team in the Inter-Allied Games, an Olympic-style competition between the Allied troops. He was discharged in 1919 as a first sergeant.

A sprinter, Drew qualified for two different Olympics in 1912 and 1916 before enlisting in the U.S Army.

Drew didn’t compete in either Olympics. In 1912, he was injured and in 1916, it was due to the Olympics being cancelled because of World War I.

“The primary reason Howard Drew is not given the recognition he deserves comes down to one thing, he never won an Olympic gold medal,” Libow said.

“Olympic gold is, and always has been, the unquestionable standard of excellence. Howard Drew never won any Olympic medals, therefore he has been left out of the conversation of both those who rank among all the great track and field athletes and of great African-American track and field athletes.”

Drew was favored to win the 100-and 200-meter dash in the Stockholm Olympics.

After the Stockholm Olympics, Drew went on to be a collegiate athlete at the University of Southern California.

During this time, he broke multiple records, such as the 100-yard meter dash in 9.6 seconds on March, 28, 1914. In 1918, Drew was recognized in Popular Science magazine with the “the greatest speed attained by any man.”

Drew was planning to go for gold again in the 1916 Olympics, but it was cancelled because of World War I and stopped him from reaching his goal.

After not being able to compete in the 1920 Olympics once returning from the war, Drew decided to go back to focusing on his education.

He began to study law at Drake University. Once he got his degree, he passed the Connecticut bar exam and became a lawyer in Hartford, making him one of the first African-Americans to become one in the state.

To add to the accolades, he became the first African-American city clerk and also police judge in the state of Connecticut.

Libow said Drew held himself to a very high standard as an African-American during those times of segregation.

“It was clear, based on his writings in the Hartford Courant, that he wanted to change the opinion of white people that ‘there were no other Negros but domestic servants, common laborers and an indigent class afloat,’” said Libow. “He wanted to be ‘treated like a man’ and as a lawyer I’m sure he felt he could serve his community, be a role model for young black men and to disprove the common perception of what a black man was capable of becoming.”

In one of Drew’s Hartford Courant articles in 1930, he said white people “felt that there were no other Negroes but domestic servants, common laborers, and an indigent class afloat.”

Drew passed away in February 1957. Although he had a unique life, there hasn’t been much recognition to honor him. In Connecticut and Los Angeles, there isn’t anything that honors and celebrates him and the life he has had. On May 13, 2016, Springfield Central High School honored Drew by naming their track after him.

Libow said that it is disappointing a man of Drew’s caliber isn’t as known as he should be.

“Howard Drew was, and remains, a role model,” Libow said. “As the ‘total package’ of athlete, Olympian, multiple World Record holder, Civil Rights advocate, track coach, track official, scholar, author, attorney and judge.”