By Melissa Nunez and Matt Gad, SCSU Journalism students

Melissa Nunez and Matt Gad, journalism students at Southern Connecticut State University, reported this story in 2017 as part of Journalism Capstone coursework on World War I.

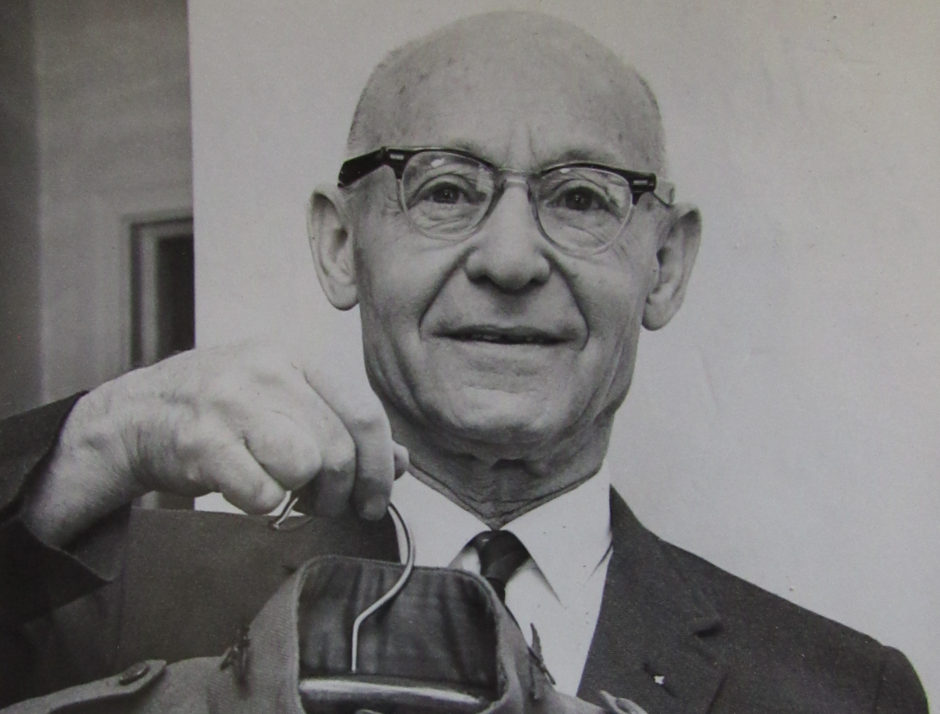

Though he didn’t see much combat, Hartford resident 2nd. Lt. Hyman Block had some close calls in the air during World War I as a pathfinder in military aviation.

“One time I found myself going right off toward another plane. I saw him just at the last moment, I zoomed up, right out of his way,” said Block in his autobiography, “I Flew with the 89th Aero Squadron.”

“Another time I fell into a tailspin—the instructor told me to fly quite shallow with my engine throttled down, and I flew a bit too shallow and went down in a tail spin at about 400 feet,” Block wrote. “Fortunately, I pulled out of it.”

Marilyn Gluck, Block’s daughter, said his orders were to primarily fly, take aerial photos for “reconnaissance” and to train other pilots.

“He was alone in the plane, there were no navigators, there was just a pilot. He waved to the other pilots and the Germans and befriended a lot of them,” said Gluck.

In the infancy of military aviation in 1912, it was hard to tell the significance flying would have in battle. As war spread throughout Europe in 1914, other nations began to organize their first air forces, according to “Eyes all over the sky: the significance of aerial reconnaissance in the First World War,” by James Streckfuss.

Block enlisted into the U.S. Air Service in August 1917 and was assigned to the Signal Corps in Mineola, Long Island. After finishing his training at the Princeton University School of Military Aeronautics and at the Rockwell Field in San Diego, Calif. in February 1918, Block was assigned overseas and was bound to Le Havre, France, according to his military service record.

Upon arriving in Le Havre in March 1918, Block and another pilot decided to break from the group and find their way by themselves.

Years after Block’s passing, Carol Levarek, Block’s granddaughter, found his journey through France “comical” and said the excursion was something that was “typical” of him.

“We had no orders in our hands and we had no idea where the train was going. Due to a mix-up of two or three hours between Le Havre time and our own watches, we got on a midnight train thinking, ‘well, this may be our train, we don’t know where we’re going, but we’ll take it anyway,’” said Block in his autobiography.

Gluck said Block was a skilled pilot with “no fear” and when he got older, he took an interest in the air shows in Rhinebeck, N.Y. She said it was not until she stumbled onto a photo of him behind the controls of a plane in his 80s that she discovered he was still flying.

“We never knew until when he was dying and I found a picture of him with a helmet on behind the controls of the plane and I said, ‘what is this.’ [He said,] ‘he was a stunt pilot and I went up with him and he let me fly the plane.’ I said, ‘Dad, are you nuts?’ He said, ‘well, if I have to die, quick and dirty.’”

Block said he enjoyed doing maneuvers in the air and was thrilled upon receiving De Havilland DH 4 planes in September 1918, as they were a vast improvement from Avion Renault planes they were used to.

“The [Avion Renault] was the ‘flying coffin’ to the French. Any fast maneuvering and the plane would fall apart,” said Block in his autobiography. “The [De Havilland] DH 4 was a very sturdy, substantial plane. I enjoyed paling along, idling the engine and holding the plane level until it stalled and then let it nose dive. I got a thrill out of it, like going down a roller coaster. I don’t know if the fellow in the back seat enjoyed it as much as I did, but I used to love doing that.”

Block said he originally sought to have a life-long military career, but it was after being discharged on April 1919 when he decided he would build a different life for himself.

“Originally when I enlisted I thought I would make a career of flying, as I felt it had a wonderful future,” said Block in his autobiography. “However, the life expectancy was too short— after seeing so many of my friends killed here and there, I felt the better part of valor would be to give up flying, which I did.”