By Jodie Mozdzer Gil and Cindy Simoneau, Southern Connecticut State University Journalism professors

Jodie Mozdzer Gil and Cindy Simoneau reported this story in 2016 as part of their instruction of the Journalism Capstone on World War I.

When Milton Peck Bradley was called to service in the U.S. Naval Reserve in July 1917, he was deployed only six miles from his home in Branford.

Bradley, a 20-year-old quartermaster second-class, was stationed on the U.S.S. Gem, a private yacht commandeered by the Navy to patrol the U.S. coast and conduct research.

Starting service in New Haven harbor, the U.S.S. Gem was later assigned to experimental work under the Submarine Defense Association in New York, New London and Newport, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

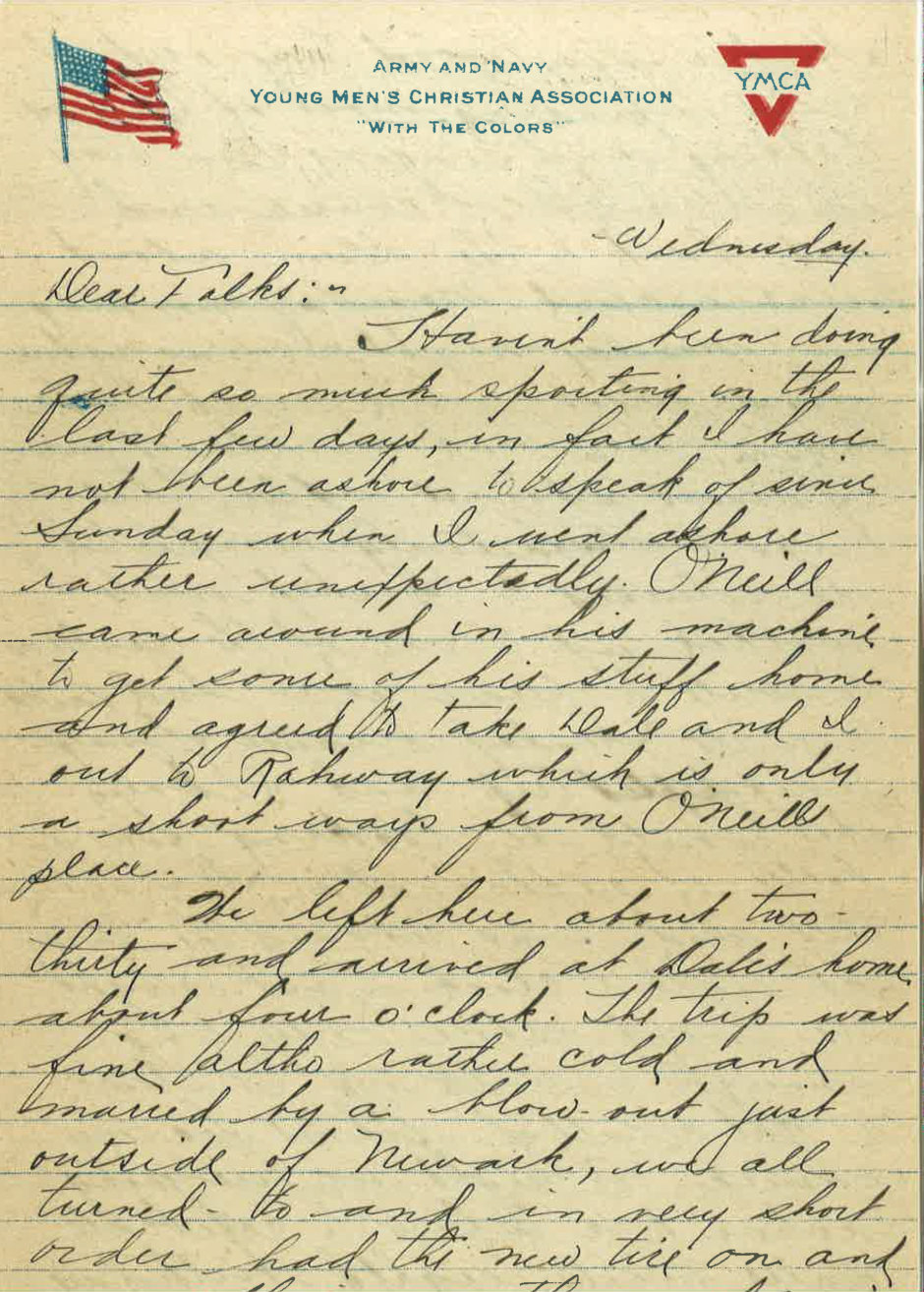

Bradley’s service, detailed in dozens of letters sent home, is part of the larger picture of what it meant to be part of the war effort.

“We talk so much about the soldiers who fought on the front, without recognizing there were people who served at home as well,” said Christine Pittsley, the project manager for the Connecticut State Library’s Remembering World War I project.

Some of Bradley’s letters, documents and photographs have been cataloged by the Remembering World War I project.

Bradley’s letters document the mix of activities conducted by his unit. The Submarine Defense Association, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command, helped experiments with camouflage defense and submarine detection devices, and conducted tests of other fuel and technology being developed at the time.

“Milton covered the gamut, from being on the ship, and being in the convoys, and going into the city to see shows,” said Nancy Bradley, who is married to Milton Bradley’s grandson.

Nancy Bradley and her husband inherited the box of letters and war photographs, sharing them with Milton Bradley’s two daughters, Carol Gesner and Nancy Kahl.

Gesner said her father never spoke of his service during the war, and they only recently started reading through the letters.

“Nobody ever talked about it,” she said. “It’s strange when you look back, but that’s the way it is.”

Gesner and Kahl said they were struck by the amount of information Milton Bradley included in his letters, contrasting them to the heavily censored letters the family received from her brother Robert during World War II.

In one letter, dated Oct. 14, 1918, Bradley details a convoy shipping off to Europe.

“It is a wonderful sight to see those ships go out one after the other until they are lost in sight over the horizon, one long broken line of monsters carrying from three thousand to ten thousand, or possibly more, men,” Bradley wrote. “The procession is headed by three or four darting seaplanes who circle all around first miles ahead, then they appear off to one side, disappear again(!) and then come flying up from the rear. These with a couple of observation balloons constitute the aerial part and probably the most sensational feature.”

“Next, and well in the advance,” he continued, “you sight a couple of our formidable destroyers scanning the surface for periscopes, and they surely make a fine appearance steaming along from twenty to thirty-five knots an hour and a very poor object for a ‘sub’ to come in contact with. Near the head of the column, there are always a few sub-chasers spread out on either side, always on the alert and battling with the sea for their lives. Then comes the transports, no two of the same design, and made distinctly individual by their camouflage and representing the shipping architecture of nearly every nation in the world.”

The transport ships were covered with troops “anxious to get the last look at America,” Bradley wrote.

In the same letter, Bradley describes watching an observation balloon become untethered from the ship, and fly straight up into the air. Though his crew watched for the balloon to come down, they never saw it, or the person in it, again. Moments later, they received word that one of the seaplanes had gone down into the water, and its three occupants needed rescuing. Though the crew of the U.S.S. Gem searched, along with other ships and two more seaplanes, Bradley said they couldn’t find the men. Other ships continued the search after dark, he noted.

Other days were not as adventurous.

“Yesterday we did nothing as usual. I sold Liberty [Bonds] from four until eight this morning,” an undated letter reads. “I had no place in particular to go, so turned in at night and slept until seven this morning. We have done some wonderful sleeping since we have been down here, anyway.”

The letters, however, detail the efforts to sell war bonds, explore the ports and travel to different locations.

Milton Bradley returned home after the war, and became an active businessman in Branford.

“That was typical of my dad – he was always the head of something. He wasn’t just a member. He would be the chairman,” said Kahl. “He was the president of his own bank. Chairman of the Board of Education in Branford. Rotary Club. He had good training in the service.”